1 Introduction

Fighting poverty consists of one of the main objectives of any development agenda. The importance of this goal has led to refinement in the measurement of deprivation, with a central role of household income or consumption to reflect household’s well-being. The development of objective measures to reflect poverty based on monetary metrics has been profuse in the economic literature, as well as the discussion about its limitations (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2016). This approach also has a long tradition in Latin American countries (Altimir, Reference Altimir1981; Gasparini et al., Reference Gasparini, Cicowiez and Sosa Escudero2013; ECLAC, 2019; among others).Footnote 1

On a somehow parallel path, scholars have attempted to measure subjective well-being based on respondent’s self-assessments in survey questions. A popular approach to collecting subjective data on poverty consists of asking for a money-metric of subjective welfare. As in the objective approach, the underlying assumption is that it is possible to make interindividual welfare comparisons on the poverty/non-poverty threshold. The most widely used approach is based on the minimum income question (MIQ) that asks what income level does the person consider to be absolutely minimal, in the sense that with less she or he could not make ends meet (see among others, Goedhart et al., Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977; Van Praag et al., Reference Van Praag, Goedhart and Kapteyn1980; Danziger et al., Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984; De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991).Footnote 2 Theses subjective questions are used to calibrate an interpersonally comparable welfare function based on observed covariates which are assumed to be relevant (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010). Potential limitations of subjective measures arise from response errors, random discrepancies in the interpretation of the survey questions, idiosyncratic differences in the respondents’ moods, and differences in tastes and personality, among others.

Efforts to integrate the subjective and objective approaches, based on the idea that income-based objective welfare indicators may fail to account for important socioeconomic factors that could affect the level of a household’s well-being, have found relatively higher levels of aggregate poverty under the subjective approach. They have also detected significant differences in the poverty profiles derived from these measures (Ravallion & Lokshin, Reference Ravallion and Lokshin2002; Lokshin et al., Reference Lokshin, Umapathi and Paternostro2006). This divergence may hide relevant information for our understanding of poverty. More specifically, objective poverty lines often imply that larger households are poorer, but this is not typically the case in studies under the subjective approach, which implies greater economies of scale than normally assumed (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010).

In Latin America, the tradition of poverty measurement has been based on the comparison of objective absolute poverty lines with income data obtained from household surveys. The pioneering work of Altimir (Reference Altimir1979, Reference Altimir1981) set the grounds for the measurement of the cost of basic food and nonfood needs, and at present most countries in the region calculate their own official poverty indicators using objective absolute poverty lines. Although poverty has been at the center of the region’s research agenda for many years (Amarante et al., Reference Amarante, Rossel and Brum2018), subjective poverty has not been widely addressed. Some studies have considered the welfare-relevant information contained in subjective measures (Herrera, Reference Herrera2002; Luchetti, Reference Lucchetti2006; Rojas & Jiménez, Reference Rojas and Jiménez2008; Scalese, Reference Scalese2022), but comparative analysis at the country level remains missing.

This Element examines the economic foundations of objective and subjective approaches to poverty measurement, focusing on seven Latin American countries: Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay. We estimate household-specific subjective poverty lines (SPL) for each country and analyze the overlap between objective and subjective poverty identification methods. For each country, we compare poverty profiles derived from both objective and subjective thresholds. It is important to note that our primary analysis is based on national objective poverty lines and national SPLs, which are not directly comparable across countries. Consequently, we do not conduct cross-country comparisons of poverty levels. However, for robustness purposes, we also consider comparable objective poverty lines calculated by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and also the ones proposed by the World Bank.

Our study contributes novel empirical evidence to the field of poverty research in several key aspects. It provides one of the first systematic comparisons of subjective and objective poverty measures across multiple Latin American countries, filling an important gap in the regional literature. By using recent data and rigorous methodologies to estimate SPLs, we contribute to the understanding of how individuals in different contexts perceive their economic needs. We examine the overlap and divergences between subjective and objective poverty measures, shedding light on the factors that may influence discrepancies between these measures. Our analysis of how household characteristics and broader economic conditions may affect perceptions of poverty provides insights into the determinants of subjective poverty. By considering both national and internationally comparable poverty lines, we offer a nuanced perspective on how different thresholds may affect poverty measurement. Furthermore, we explore the implications of our findings for policy formulation, suggesting how the integration of subjective and objective measures could inform more effective poverty-reduction strategies.

Additionally, we reflect on the implications of incorporating subjective poverty measurements into broader poverty discussions and the design of poverty alleviation policies. In doing so, this study seeks to contribute to a more informed debate about the multifaceted nature of poverty and how it can be most effectively measured and addressed in the Latin American context.

This Element offers several methodological contributions. We employ a rigorous approach to estimating SPLs, building on and extending previous work in this area. Our use of household-specific SPLs illustrates how perceptions of poverty vary across different household types and socioeconomic contexts. Furthermore, our comparative analysis across seven countries provides insights into how the relationship between subjective and objective poverty measures may vary in different national contexts.

From a theoretical perspective, our study contributes to ongoing debates about the nature of poverty and how it should be conceptualized and measured. By examining the divergences between subjective and objective measures, we shed light on the complex relationship between material deprivation and perceived economic well-being. This analysis has implications for how we understand the multidimensional nature of poverty and the potential limitations of relying solely on income-based measures.

The remainder of this Element is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive discussion of objective and subjective approaches to poverty measurement, examining their theoretical foundations, comparative advantages, and limitations. Section 3 addresses the methodological considerations in establishing objective and SPLs. Section 4 synthesizes the existing literature on subjective poverty, with particular emphasis on Latin American studies. Section 5 outlines our data sources and methodological framework. Section 6 presents a comparative analysis of subjective and objective poverty measures across the seven countries in our study. Section 7 examines the discrepancies between objective and subjective poverty measurements and investigates their underlying determinants. Section 8 explores the relationship between consumption patterns and subjective poverty. Finally, Section 9 concludes with policy implications and directions for future research.

By providing a comprehensive analysis of subjective and objective poverty measures in Latin America, this study aims to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of poverty in the region and to inform more effective poverty-reduction strategies. Our findings have implications not only for academic debates about poverty measurement but also for policymakers seeking to design and implement more targeted and effective anti-poverty programs.

2 Objective and Subjective Approaches to Poverty

2.1 Objective Approach

Poverty alleviation is a concern shared by various social actors, including academics, and the identification of people living in poverty becomes crucial to think about the design and implementation of policies aimed at this end. With this objective in mind, a relevant step is the identification of people living in poverty. Academic debates on this subject have a long history, dating back to the late nineteenth century and the discussion about how to reflect the insufficiency of income to cover basic needs for the fulfillment of mere physical efficiency. This early approach is founded on the idea of objectivity, implying that there is a certain reality which can be captured by a specific measure. Poverty is confined to the material aspects of life and a monetary metric is needed to reflect the phenomenon. The origins of this approach can be traced to the contributions of Booth and Rowentree, who documented the living conditions of England’s poor in the cities of London and York during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This is still the approach with the largest development in economics (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010) and allows for multiple non-income dimensions of welfare, reflecting an absolute view in the space of welfare. The formalization of the approach assumes a utility function for individual i of the form

![]() , where

, where

![]() is a vector of the quantities of commodities consumed and

is a vector of the quantities of commodities consumed and

![]() is a vector of non-income characteristics which are relevant for welfare, including demographic characteristics of the household. The utility maximizing consumption vector is denoted

is a vector of non-income characteristics which are relevant for welfare, including demographic characteristics of the household. The utility maximizing consumption vector is denoted

![]() at price vector

at price vector

![]() and total expenditure on consumption

and total expenditure on consumption

![]() . The implied indirect utility function is

. The implied indirect utility function is

![]() , which gives the maximum attainable welfare at the prevailing prices and characteristics and can be inverted to get the expenditure function

, which gives the maximum attainable welfare at the prevailing prices and characteristics and can be inverted to get the expenditure function

![]() . This function gives the minimum cost of utility u for person i when facing prices

. This function gives the minimum cost of utility u for person i when facing prices

![]() .

.

If the minimum utility necessary to escape poverty is denoted

![]() , the welfare consistent poverty lines are given by

, the welfare consistent poverty lines are given by

![]() , which can in turn be rewritten as

, which can in turn be rewritten as

![]() . This equation reflects that the welfare consistent poverty line is the cost of a bundle of basic consumption needs given by the vector of utility-compensated demands at the reference level of utility defining who is poor in the welfare space. The poverty rate is then the proportion of population whose incomeFootnote 3 is below the poverty line,

. This equation reflects that the welfare consistent poverty line is the cost of a bundle of basic consumption needs given by the vector of utility-compensated demands at the reference level of utility defining who is poor in the welfare space. The poverty rate is then the proportion of population whose incomeFootnote 3 is below the poverty line,

![]() In other words, a person is identified as poor if their household income is below a certain monetary threshold. At present, most absolute poverty thresholds reflect an income level that covers not only the minimum nutritional requirements for good health and a normal level of activity but also the goods and services that cover other needs.

In other words, a person is identified as poor if their household income is below a certain monetary threshold. At present, most absolute poverty thresholds reflect an income level that covers not only the minimum nutritional requirements for good health and a normal level of activity but also the goods and services that cover other needs.

It is important to notice that this framework allows for a measure of absolute monetary poverty, as the one undertaken in this study, but it is also consistent with relative monetary poverty measurement, and with the measurement of nonmonetary poverty. These three measures (absolute, relative, and nonmonetary) are part of the objective approach to poverty measurement.Footnote 4 In the case of relative income, it is possible to assume that the vector of non-income characteristics which are relevant for welfare,

![]() , includes mean income of some reference group.

, includes mean income of some reference group.

Moreover, Ravallion (Reference Ravallion2010) has argued that the objective framework is consistent with the measurement of poverty as deprivation in terms of a persons’ functionings, as proposed by Sen’s (Reference Sen1985) influential work. This would imply considering that poverty is the situation of not having sufficient income to support specific normative functionings. Nevertheless, most studies of deprivation under the capability approach have taken alternative paths, considering multidimensional deprivation based on the Alkire–Foster multidimensional counting approach (Alkire & Foster, Reference Alkire and Foster2007, Reference Alkire and Foster2011). This implies identifying the multidimensionally poor based on a two-stage process in which a threshold is defined for deprivation in each dimension and then a second cutoff is established to determine the number of dimensions in which someone is required to be deprived to be identified as multidimensionally poor. None of these two stages implies the consideration of equivalent income to fulfill a certain functioning.

As discussed, the measure of poverty through a monetary-based method can be built upon an absolute or a relative poverty line. The absolute poverty line is set in reference to the cost of a basic food basket plus a given sum for covering nonfood needs, referring to certain elements required to survive, such as clothing or shelter. The alternative is to use a relative poverty line that is set based on the comparison with a reference group. In general, this is defined with reference to a certain point in the income or expenditure distribution. For instance, European countries use this approach and consider the poverty line as equivalent to 60 percent of median equivalized household income.

In any case, the objective approach is based on the idea that poverty is confined to material aspects of life and can be measured based on information about these aspects. The differences within this approach are on whether the command is over commodities or over what an individual can and cannot do in life and on the importance of the reference group to establish the poverty threshold.

2.2 Criticisms to the Objective Approach

The objective approach to poverty implies that there is a certain reality “out there” which can be captured through certain statistical methodologies (Ruggeri Laderchi et al., Reference Ruggeri Laderchi, Saith and Stewart2003). The idea of being able to capture and monitor the situation of the population with regard to poverty is undoubtedly appealing. But when moving on to the action of poverty measurement, a big number of (very) relevant assumptions are needed, and this leads to questioning the claim of objectivity of the measurement. There are value judgments involved, which can be made explicit or subject to sensitivity analysis by the researchers. In any case, it is difficult to consider the measurement as purely objective and completely free of biases. In what follows, and given the scope of our study, we concentrate on the main criticisms of the objective approach to poverty based on absolute monetary poverty lines. The expert-based definition of food baskets and poverty lines has been considered as a rather paternalistic procedure to define a socially acceptable poverty line (Van Praag & Ferrer Carbonell, Reference Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell2005).

It is true that the underlying assumptions are derived from economic theory, but most of these assumptions cannot be tested or evaluated. Some of the controversial aspects involved include the technical rules for the determination of food requirements, the definition of the essential consumption basket, the issue of how to price comparable goods in different regions, the treatment of different housing situations, and the adjustment of needed resources according to household size and composition. Besides all these technical aspects, the objective monetary method does not consider that household income or expenditure is endogenous to its preferences and needs (Sen, Reference Sen1985). Households may prefer to reduce the hours of work if they value leisure over consumption, and this may lead to considering these households as income poor, even if they do not consider themselves poor because of their valuation of leisure.

The objective approach, based on external value judgments, completely ignores the real perception of the poor. The convenience of complementing the expert-derived poverty thresholds with views that consider the insider’s perspectives and people’s perceptions about their own poverty status has received significant support from academics. Among others, Deaton (Reference Deaton2010) has underlined that people themselves have a very good idea of whether they are poor, and so their opinions should be considered. In his words, “there is something to be said for directly asking people around the world how their lives are going, whether they have enough, or whether they are in financial difficulty, and in cases where there are reliable income data, turning those reports into poverty lines” (Deaton, Reference Deaton2010). A few sentences written by the most prestigious poverty researchers suffice to illustrate the simplification implied by the pretension of complete objectivity in poverty measurement (see Box 1).

Box 1 Objectivity in Poverty Measurement

One cannot completely eliminate the value judgements inherent in the construction of poverty thresholds, we should try to make the ad hoc assumptions more justifiable. (Kakwani, Reference Kakwani2010, p. 36)

The choice of reference group should be determined on the basis of the commitment the governments want to make in terms of allocating resources to poverty reduction programs. (Kakwani, Reference Kakwani2010, p. 39)

In the end, a judgment is invariably required as to whether the implied lines seem reasonable in the specific setting. (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010, p. 11)

What one is doing in setting an objective poverty line in a given country is attempting to estimate the country’s underlying social subjective poverty line. (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010, p. 24)

Importance of testing the sensitivity of poverty comparisons to the choice of reference, as it determines the level of the poverty line. (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2012, p. 6)

There is “scope for debate at virtually every step” in generating objective poverty measures. (Ravallion & Lokshin, Reference Ravallion and Lokshin2001, p. 338)

2.3 Subjective Approach

A different approach to identify poverty situations consists in asking people about how they perceive their own welfare, whether in absolute or relative terms, and making subjective interpersonal welfare comparisons. In words of Ravallion (Reference Ravallion2010), this approach can be considered as an attempt of cross-fertilization between the antagonistic “objective-quantitative” and “subjective-qualitative” schools of poverty that dominate different academic disciplines. This approach is by far not the dominant one in poverty research, although in recent years some studies based on subjective information have emerged. The low prevalence of studies based on the subjective approach in economics derives, to a certain point, from the scarcity of these data. But it is also explained by economists’ skepticism about whether these questions elicit meaningful answers for welfare measuring, as discussed in Section 2.3.

The subjective approach measures the welfare levels of households based on their responses to “subjective” questions about their evaluations of their own economic status, instead of deriving utility-based measures from market behavior. Then, a poverty threshold is derived in the monetary space, defined as the income level at which some critical level of subjective welfare is reached in expectation.

The departing point of the subjective approach is the theory of consumer behavior developed by Van Praag (Reference Van Praag1968), based on the idea that the individual can evaluate his welfare position with respect to their income level on a bounded scale. This approach is in the tradition of cardinal utility, as opposed to the possibility of only being able to order according to (ordinal) preferences. It allows for the derivation of an individual welfare function of income or cardinal utility function of income, which measures only the individual relative welfare as perceived by the individual. Each individual has his or her own individual welfare function. It is measured as a proportion between the current welfare and the welfare that could be in the optimal imaginable situation. Welfare is approximated by income and the welfare function is evaluated on a 0 to 1 scale.

The pioneering work of Van Praag (Reference Van Praag1971) and Van Praag & Kapteyn (Reference Van Praag and Kapteyn1973) at the University of Leyden was developed within this framework, attempting to verify the operationality of the theory proposed in Van Praag (Reference Van Praag1968) and to estimate the welfare function of income for a sample of individuals. Besides the theoretical formulation, they provide empirical illustrations based on a specific question included in consumer union surveys for Belgium and the Netherlands, respectively. On theoretical grounds, individuals should be provided with a series of income levels and asked to evaluate these levels in a bounded space, for example, on a 0 to 1 scale. This is a complex exercise, as it would be very challenging for extremely poor people to discern the differences among various high-income levels (and the other way round). The solution is to employ an indirect method, using the so-called income evaluation question, which allows to elicit an individual’s welfare judgments. Through this question, the individual is asked to determine the level of income he or she considers fits into certain categories associated to utility.

In the original work of Van Praag (Reference Van Praag1971) and Van Praag & Kapteyn (Reference Van Praag and Kapteyn1973), the categories were “Excellent,” “Good,” “Amply sufficient,” “Sufficient,” “Barely sufficient,” “Insufficient,” “Very insufficient,” “Bad,” and “Very bad.” By answering, the individual gives a division of the income range into certain intervals. The answers to this question are transformed into numbers on a 0 to 1 scale, under the assumption that the individual partitions the income range according to equal percentiles of the welfare function. This information allows to estimate the individual welfare function of income, which is represented through a lognormal distribution and whose welfare parameters

![]() and

and

![]() may differ between individuals. Different exercises have considered welfare levels between 0.4 and 0.6 on a 0 to 1 scale to set the poverty line (Goedhart et al., Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977; Van Praag et al., Reference Van Praag, Spit and Van de Stadt1982). According to Van Praag et al. (Reference Van Praag, Spit and Van de Stadt1982), a level of 0.5 means approximately that a family is called poor if it evaluates its income as barely sufficient or less.

may differ between individuals. Different exercises have considered welfare levels between 0.4 and 0.6 on a 0 to 1 scale to set the poverty line (Goedhart et al., Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977; Van Praag et al., Reference Van Praag, Spit and Van de Stadt1982). According to Van Praag et al. (Reference Van Praag, Spit and Van de Stadt1982), a level of 0.5 means approximately that a family is called poor if it evaluates its income as barely sufficient or less.

The underlying idea is that a society and its policymakers can stipulate a certain minimum welfare evaluation below which citizens should not fall. The income levels corresponding to those minimum welfare evaluation levels defines the poverty threshold. The computation of the corresponding minimum income levels for each individual in order not to fall below that minimum welfare according to their welfare function of income is straightforward and allows the estimation of national SPLs.

The other approach to build a SPL consists of asking only one income amount that corresponds to a specific welfare label, instead of asking several income levels that correspond to several welfare levels – as done through the income evaluation question. This question is called the MIQ and can be conceived as a simplified version of the income equivalent question (see Flik & Van Praag, Reference Flik and Van Praag1991). A typical formulation of the MIQ question is: To meet the expenses you consider necessary, what do you think is the minimum income, a family like yours needs, on a yearly/monthly basis, to make ends meet?.Footnote 5 A similar question with an alternative wording is the minimum spending question: In your opinion, how much would you have to spend each year/month in order to provide the basic necessities for your family? (see Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003).

The “MIQ” seeks to get the respondent to declare what the minimum income would be he or she considers necessary for his or her household to “make ends meet.” Of course, the response to this question is influenced by several idiosyncratic and psychological factors, so it is not one’s stated perception of own welfare that is taken to be the relevant welfare metric. Instead, the subjective question provides information for the identification of a metric of welfare, including the setting of SPLs. In sum, these subjective questions are used to calibrate an interpersonally comparable welfare function based on observed relevant covariates (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010).

This implies that it is necessary to estimate a model with the answer to the MIQ as the dependent variable and the household income, together with other characteristics of the person or household that are considered important, as regressors. The result of the estimation is equated with the household income, to subsequently clear the value of the income that defines the SPL. Thus, all households below this line are considered poor. As underlined by Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Yip and Law2020), it should be noted that although the SPL has been classified as a subjective approach, it in fact stands somewhere between the economic approach of measuring poverty by monetary indicators set by outsiders and the subjective approach of asking respondents to assess their own degree of poverty.

The “MIQ” had its first applications in the works of Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977), Van Praag et al. (Reference Van Praag, Goedhart and Kapteyn1980, Reference Van Praag, Spit and Van de Stadt1982), Danziger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), Colasanto et al. (Reference Colasanto, Kapteyn and Van der Gaag1984), Kapteyn et al. (Reference Kapteyn, Kooreman and Willemse1988), and De Vos & Garner (Reference De Vos and Garner1991). In this Element, we use this strategy to build SPLs for Latin American countries. The methodological details for the estimation of SPLs are discussed in Section 3.

2.4 Criticisms to the Subjective Approach

The extent to which subjective perceptions of individuals really reflect objective social conditions is a contented issue driven and encouraged by the famous Easterlin paradox which argues that when a country’s income increases, happiness does not increase (Easterlin, Reference Easterlin, David and Reder1974).Footnote 6 One potential reason for this paradox is that individuals evaluate their well-being in relation to other groups or points in time, although this remains an open debate (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2005; Di Tella & MacCulloch, Reference Di Tella and MacCulloch2008; Clark, Reference Clark2018).

Focusing on the more specific issue of subjective poverty measurement, critiques are also abundant. One strand of literature poses theoretical critiques to the welfare income function. Seidl (Reference Seidl1994) questions that the utility function of income is bounded from both below and above and criticizes the idea that a utility function of money has a convex–concave form. Van Praag & Kapteyn (Reference Van Praag and Kapteyn1994) respond to the first critique by providing counterexamples of bounded utility functions, such as those used in the literature on decisions under uncertainty (Arrow, Reference Arrow1971). In relation to the second critique, Van Praag & Kapteyn (Reference Van Praag and Kapteyn1994) defend the proposal of a convex–concave or sigmoid form of the utility function, arguing that for extremely poor people, an extra dollar brings them closer to survival, implying that the utility function would be convex shaped until the individual exceeds the situation of poverty.

But most critiques refer to the underlying assumption that everyone ascribes the same welfare meaning to the concept of “minimally necessary income.” If the answers to the MIQ s are related to differences in lifestyle and not to actual costs or needs, their use for poverty assessment is questionable. Garner & De Vos (Reference Garner and de Vos1995) include expenditure in the estimation of the subjective thresholds and compare respondents from the United States and the Netherlands, finding that the US respondents were thinking about their current expenditures and lifestyles, rather than their “basic needs” when answering the question. This implies that the assumption that everyone adheres the same welfare connotation to a “minimally necessary income” may not be valid across surveys or between and within populations, posing a doubt about the measurement of subjective poverty. On the same line, in the case of the Leyden poverty line, it is necessary to assume that people can evaluate income levels in general and their own income in terms of “good,” “bad,” “sufficient,” and so on. It is also assumed that the verbal labels can be translated into a utility function that is bounded on a 0 to 1 scale.

Another potential limitation is the possibility that the measure of income obtained from the survey for calculating a SPL may not be consistent with what respondents have in mind when they answer the MIQ. The method assumes that every respondent gives the same welfare meaning to the phrase “minimally necessary income,” an assumption not always backed by the evidence (Garner & De Vos, Reference Garner and de Vos1995). The survey-based income is estimated considering many questions covering a wide range of potential sources of income, and the respondent builds his or her income by systematically considering these different sources. The MIQ assumes that the respondent already knows its income and can bring a precise response to a unique question. Additionally, households may have different concepts of income that may not correspond to the concept of income of the MIQ. Special components of income such as cash income, imputed rent, or income from own production activities are of particular concern in relation to these divergencies. Given these issues, Pradhan & Ravallion (Reference Pradhan and Ravallion2000) conclude that there are serious difficulties in obtaining sensible answers to the usual MIQ in most developing countries, and they propose a method to retrieve the SPL from some qualitative questions on perceived consumption adequacy added to an integrated household survey.

On the same line, if self-assessment of well-being reflects aspirations rather than real circumstances, and if these aspirations are influenced by how own’s situation compares to well-being of other households, the measurement of subjective poverty may not be clear-cut.

In their discussion about the limitations of subjective data, Bertrand & Mullainathan (Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2001) conclude that experimental evidence supports the idea that cognitive effects (ordering of questions, wording, etc.) affect the way people answer subjective questions. This casts doubts about the use of variables originated from subjective questions as dependent variables, as measurement error seems to be correlated with characteristics and behaviors. On a similar line, Ravallion & Lokshin (Reference Ravallion and Lokshin2002) indicate that personality traits may influence how people respond to subjective welfare questions, so we would need to control latent psychological differences to identify welfare levels.

A more positive view about the use of subjective data and the calibration of subjective poverty measures is given by Ravallion (Reference Ravallion2010), who underlines the trade-offs between the problems inherent to subjective data and the welfare relevant information that it may contain.

3 The Definition of Objective and Subjective Poverty Lines

A poverty line represents a relevant threshold in any society and the setting of this line involves a political decision (Goedhart et al., Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977). The establishment of a poverty line implies normative options that may go beyond technical aspects. There are not internationally validated standards that can be applied in all contexts, so the setting of a poverty line invariably implies a certain degree of arbitrariness (Deaton, Reference Deaton1997). Moreover, the discussions and deliberations of poverty thresholds take place within the framework of historical processes and specific contexts, where national and international institutions and organizations also play an important role. The decisions made when setting the poverty threshold may have implications in terms of public policies and access to public benefits.

On economic grounds, the poverty line should reflect the costs of attaining a certain standard of living, and this minimum level of welfare can be identified based on an objective or a subjective approach, as discussed in Section 2.3. Within each approach, there is a broad set of decisions that must be made to set the line in each context, and these decisions have impact on the results obtained.

Following Ravallion (Reference Ravallion2010), the main methods found in developing countries to set absolute poverty lines are the food-energy intake method and the cost of basic needs method.Footnote 7 The food-energy intake method consists of finding the consumption expenditure or income level at which food-energy intake is just enough to meet the requirements for good health and normal activity levels. Using expenditure and consumption surveys, the population is ordered in terms of income, and a group is identified as the first one for which the minimum nutritional requirements for a healthy life and normal activity are met.Footnote 8 The calorie consumption of households is calculated based on the food items purchased, and to incorporate the fact that caloric intakes vary for a certain level of income, the method generally calculates an expected value of intake, given the level of income. The average income or expenditure of the group of households selected as the reference group is considered the poverty line. This method does not imply the establishment of the basket of goods that allows the minimum nutritional requirements, nor the specification of the items included in nonfood consumption. Concerns about this method refer to the fact that the relationship between food-energy intake and income may change with differences in tastes, activity levels, relative prices, and publicly provided goods, among others (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2010). For example, the real income at which an urban household may attain a given caloric requirement can be higher than the corresponding one for a household in rural areas.

The cost of basic needs method consists of the establishment of an adequate consumption basket to cover certain basic needs, including food and nonfood items. The poverty line is established as the cost of the basic basket for each subgroup (generally regions) of the population; this implies selecting a group of households of a certain part of the income distribution (low income). In contrast to the food-energy intake method, instead of using the average expenditure of this group as the poverty line, the food they consume is chosen as a basic food basket. This basket of goods implies the incorporation of demand behavior for the satisfaction of nutritional requirements. There are infinite vectors of consumption that satisfy nutritional needs, but the method chooses the one that is consistent with the consumption decisions of a relevant reference group. As a second step, items corresponding to the nonfood expenditures of the reference group are added. These items include goods necessary to meet other basic needs, such as clothing, housing, transportation, and so on. This procedure gives rise to the Orshansky coefficient, which establishes the relationship between the basic food basket and the poverty line.Footnote 9

Probably the most known poverty measure is the one proposed by the World Bank, based on a set of absolute poverty lines. Their objective is to measure poverty consistently across countries, reflecting similar levels of well-being in different countries. The original value of the World Bank poverty line was set at 1 dollar (PPP) per day by Ravallion, Datt, and Van de Walle (Reference Ravallion, Datt and Walle1991), using as reference the poverty lines used in some of the world’s poorest countries. It was then updated in 2022 to a value of US$2.15 per person per day, adjusted for purchasing power parity (2017 PPP). Since 2017, the World Bank publishes measurements based on two additional and higher lines, associated with the concepts of poverty in countries with higher incomes. The lines are $3.65 and $6.85 (2017 PPP) per person per day and were obtained as the median of the official lines for lower middle-income and upper middle-income countries, respectively, based on Jolliffe and Prydz (Reference Jolliffe and Prydz2016). In Latin America, the ECLAC calculated absolute poverty lines based on consumption baskets for the countries of the region during the 1990s, to be able to elaborate comparable overviews of poverty at the regional level. The methodology for the calculation of these poverty lines was recently updated (ECLAC, 2019).

The estimation of a SPL is based on the question ‘What is the minimum monthly income amount that you estimate is necessary to meet the basic needs of your household?’. It is important to notice that the approach is model based in the sense that a model is used to explain the interhousehold variation in the responses to survey questions; individual responses alone are not used to determine the poverty line directly. The respondent’s answer to this MIQ will be denoted as

![]() . This minimum income depends on the actual household income and a series of other factors, including, for example, the household size. The formulation, following Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977) and Danziger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), is as follows:

. This minimum income depends on the actual household income and a series of other factors, including, for example, the household size. The formulation, following Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977) and Danziger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), is as follows:

(1)

(1)

where

![]() is the actual household income and

is the actual household income and

![]() is a vector of other variables. The function

is a vector of other variables. The function

![]() is monotonically increasing in

is monotonically increasing in

![]() , and there exists an income level

, and there exists an income level

![]() defined by

defined by

(2)

(2)

such that, for all incomes

![]() less than

less than

![]() , it holds that

, it holds that

![]() , and for all incomes Y greater than

, and for all incomes Y greater than

![]() , it holds that

, it holds that

![]() . Therefore, the income level

. Therefore, the income level

![]() is a candidate for the poverty line; people with income above this level tend to feel that their income is adequate, while those below that level tend to feel that it is not.

is a candidate for the poverty line; people with income above this level tend to feel that their income is adequate, while those below that level tend to feel that it is not.

The approach was originally designed for use with panel data (Kapteyn et al., Reference Kapteyn, Kooreman and Willemse1988), which allowed to test whether people gravitate toward some true minimum over time. It is expected that respondents who are above the true minimum would find that over time they have a better idea of what their true minimum is and would respond accordingly. For those below the true minimum, over time they would realize that they are underestimating their true income needs. However, most empirical applications of the SPL based on MIQ are based on cross-sectional data. The rationale behind choosing the intersection of the function

![]() with the line

with the line

![]() , represented by

, represented by

![]() , is that only households for which income is equal to their minimally necessary income have realistic perceptions of this minimum income level (Kapteyn et al., Reference Kapteyn, Kooreman and Willemse1988). Households with higher income are likely to overestimate their minimally necessary income, while those with lower income are expected to underestimate it (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991).

, is that only households for which income is equal to their minimally necessary income have realistic perceptions of this minimum income level (Kapteyn et al., Reference Kapteyn, Kooreman and Willemse1988). Households with higher income are likely to overestimate their minimally necessary income, while those with lower income are expected to underestimate it (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991).

In line with Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977), Danziger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), and De Vos & Garner (Reference De Vos and Garner1991), a linear-logarithmic form is used to estimate equation (1). In addition to the logarithm of household income, other explanatory variables (x) are included. First, household size is an important factor in determining

![]() , as larger families will require a higher

, as larger families will require a higher

![]() . Moreover, in the case of the United States, it has been observed that

. Moreover, in the case of the United States, it has been observed that

![]() is lower for female-headed households (Danziger et al., Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), while it increases with age, at a decreasing rate (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991). These authors also highlight the relationship between variables such as education, ethnic background, marital status of the household head, household composition, and the values of

is lower for female-headed households (Danziger et al., Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984), while it increases with age, at a decreasing rate (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991). These authors also highlight the relationship between variables such as education, ethnic background, marital status of the household head, household composition, and the values of

![]() (Garner & De Vos, Reference Garner and de Vos1995; Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003). Additionally, the area of residence is also a factor to consider since household needs can vary depending on the environment they are situated in (Colasanto et al., Reference Colasanto, Kapteyn and Van der Gaag1984; Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003).

(Garner & De Vos, Reference Garner and de Vos1995; Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003). Additionally, the area of residence is also a factor to consider since household needs can vary depending on the environment they are situated in (Colasanto et al., Reference Colasanto, Kapteyn and Van der Gaag1984; Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003).

Based on the log-linear expression of equation (1), finding a subjective poverty threshold implies calculating the

![]() as the intersection of the relationship:

as the intersection of the relationship:

(3)

(3)

Therefore, by equating for

![]() for different values of

for different values of

![]() , the value of

, the value of

![]() , the subjective poverty threshold, is defined as

, the subjective poverty threshold, is defined as

(4)

(4)

4 Previous Research about Subjective Poverty

Research on subjective poverty started over forty years ago with the pioneering study of Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977), who settled the ground of the MIQ methodology. After them, several studies applied this methodology with different specifications of the SPL. Most of the applications in this first stage were based on US data, with some notable exceptions as Van Praag et al. (Reference Van Praag, Goedhart and Kapteyn1980) for several European countries. Later, some studies incorporated basic demographic determinants in the specification of the SPL, considering, for example, age, gender, and urban–rural location (Colasanto et al., Reference Colasanto, Kapteyn and Van der Gaag1984; Danziger et al., Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984). Further extensions included education, race, religion, disability, and marital status. An interesting strand of literature has underlined the role of previous family income and reference groups. Results indicate that households that have recently suffered a considerable decrease in their incomes report significantly higher minimum incomes than households with stable incomes (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991). Studies have also explored whether certain expenditures are considered when answering the MIQ question. Results indicate that housing and utility expenditures were considered when answering the question about minimum necessary income (De Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991; Garner & De Vos, Reference Garner and de Vos1995). Differences among European countries in terms of self-perception of poverty have been found to be related to different levels of household and community social capital endowments (Guagnano et al., Reference Guagnano, Santarelli and Santini2016).

When subjective and objective poverty thresholds are compared, the former are higher (de Vos & Garner, Reference De Vos and Garner1991; Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003). The divergence between the two poverty rates widens with household size, especially when objective poverty is measured based on per capita income. Larger households are more likely to be identified as income poor than to self-assess their status as poor. This may be explained by the lack of adjustment for lower per person costs of maintaining a given standard of living when individuals live together rather than apart. Equivalence scales implicit in subjective poverty measures tend to be greater than those usually considered in objective measures, posing interesting questions for methodological research (Ravallion & Lokshin, Reference Ravallion and Lokshin2002).

Recent applications of subjective poverty are less focused on measurement and give more attention to the determinants of subjective poverty, also considering the discrepancies between subjective and objective poverty profiles. At the same time, the focus of the applications has shifted from the United States to developing countries. An interesting exception is Zelinsky et al. (Reference Želinský, Mysíková and Garner2022), who estimate subjective poverty trends between 2004 and 2019 for 28 European countries based on the MIQ, as we do. They find poverty declines in more than half of the countries and argue that this reflects country trends that are not captured by official poverty indicators. In the case of Italy, Filandri et al. (Reference Filandri, Pasqua and Struffolino2020) find that discrepancies between objective and subjective poverty are associated with the job stability of household members.

Several recent studies estimate subjective poverty for developing countries: Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhao, Bai, Zhang and Yu2020) for Rural China, and Maruejols et al. (Reference Maruejols, Wang, Zhao, Bai and Zhang2022) for China based on MIQ, Mahmood et al. (Reference Mahmood, Yu and Klasen2019) for Pakistan and Posel & Rogan (Reference Posel and Rogan2014) for South Africa based on a ten-step ladder of the relative position of the household in the distribution (steps 1 and 2 considered as poor), and Peng (Reference Peng2021) and Peng & Law (Reference Peng and Law2023) for Hong Kong based on the self-perception of poverty.

The determinants of subjective poverty found in these studies are age and gender (male) of the household head and family size (reducing subjective poverty). Also, large and unusual expenditure on health and education tend to increase subjective poverty (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Bai, Zhang and Yu2020). The proportion of boys among children as well as residence in rural areas reduce subjective poverty, whereas unemployment, food insecurity, and physical insecurity increase it (Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Yu and Klasen2019). Both studies identify a reduction in the probability of subjective poverty as per capita household income increases but differ in the effect of human capital and household wealth and assets. While Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhao, Bai, Zhang and Yu2020) observe that subjective poverty increases with human capital and household wealth and assets, Mahmood et al. (Reference Mahmood, Yu and Klasen2019) observe a reduction in subjective poverty with education, household assets, and farmer´s land. Mauejols et al. (Reference Maruejols, Wang, Zhao, Bai and Zhang2022) propose an explanation to these contrasting results: They find that subjective poverty is mostly associated with income for low-income households, but in the case of middle-income households, subjective poverty is associated with a combination of relatively low income, low endowments (land, consumption assets), and unusual large expenditure.

All the reviewed studies that compare subjective poverty against objective poverty find that the subjective poverty is significantly higher (Posel & Rogan, Reference Posel and Rogan2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Bai, Zhang and Yu2020; Peng, Reference Peng2021; Zelinsky et al., Reference Želinský, Mysíková and Garner2022; Peng & Law, Reference Peng and Law2023). Mahmood et al. (Reference Mahmood, Yu and Klasen2019) identify education, household size, own residence, and physical security among the factors that reduce objective poverty among households below the SPL. In the case of South Africa, Posel & Rogan (Reference Posel and Rogan2014) conclude that subjective assessments of poverty are influenced by a range of factors in addition to the household’s current economic resources, including the ability of the household to generate resources in the past and in the future, the household’s access to basic services, and the average health status of household members. They also argue that these divergences are related to issues of economies of scale and adult equivalence, which deserve more attention. Alem et al. (Reference Alem, Köhlin and Stage2014) study the evolution of subjective and objective poverty for a 15-year span in urban Ethiopia and find that despite significant economic growth and a decrease in objective poverty, subjective poverty has largely stayed the same. They show that the household history in objective poverty is relevant to determining their perceptions, as households with a history of objective poverty continue to see themselves as poor, even when their material consumption improves. Conversely, employment protects against subjective poverty; households with any form of employment are less likely to perceive themselves as poor, even if they still experience objective poverty.

Some studies follow a slightly different strategy, focusing on the specific importance of one determinant of the subjective/objective poverty disagreement. One determinant that has gained increasing attention recently is the importance of social networks and reference groups as a subjective poverty determinant and as a possible explanation of the misalignment of subjective and objective poverty assessment. Peng (Reference Peng2021) studies for Hong Kong the importance of comparisons with parents and friends and finds that upward intergenerational mobility increases the probability of not feeling poor while being economically poor, and the opposite happens with downward mobility. In the case of friends, those who contrasted their social status with their lower-status friends were more likely to feel nonpoor, even if they were economically poor, and again the opposite relation is observed for those comparing to higher-status fiends. Overall, parents were a more important reference group than friends. Li & Cai (Reference Li and Cai2024) explore how social networks affect subjective poverty through social support (emotional and instrumental) and reference groups in China. They find that larger and stronger social networks reduce subjective poverty. In addition, when the social network members serve as the reference group, the higher the status of individuals in the network, the weaker the subjective poverty. The effect of social networks as a reference group on subjective poverty depends on the objective poverty condition. Specifically, when individuals are objectively poor, the positive impact of social networks as a reference group on subjective poverty is diminished. The longitudinal study for urban Ethiopia (Alem et al. Reference Alem, Köhlin and Stage2014) also finds that the relative economic position of households plays a major role in determining subjective poverty.

Another salient determinant of the discrepancy between objective and subjective poverty that has drawn recent attention is the expenditure pattern of households. Peng & Law (Reference Peng and Law2023) and Peng (Reference Peng2023) study the importance of consumption patterns in explaining subjective poverty in Hong Kong. Peng & Law (Reference Peng and Law2023) find that food-dominant consumption pattern increased the probability of feeling poor among the objectively poor as did the mortgage-high pattern among the economically nonpoor, both in reference to a balanced pattern. However, the significant association between the mortgage-high pattern and subjective poverty became insignificant after controlling for assets, indicating that this effect was most likely offset by the negative impacts of homeownership and assets. Peng (Reference Peng2023) focuses on the consumption of conspicuous goods (that display social status) and experiential goods (purchases made to acquire a life experience). He finds that spending on leisure, which encompasses both conspicuous and experiential consumption, raised the likelihood of feeling nonpoor among those who are objectively poor, and conversely decreased the likelihood of feeling poor among those who are economically nonpoor. These effects were influenced by self-perceived social status (via conspicuous consumption) but not by social connectedness (via experiential consumption).

In Latin America, studies about subjective poverty are scarce, and the existing ones are focused on one single country; no comparative studies for the region were identified. Many of them are not representative at the national level, as they are based on a specific city, region, or group of population. For Mexico, subjective poverty estimates are available for a specific region (Ortiz-Pech et al., Reference Ortiz-Pech, Alvarez -Marchan and Albornoz-Mendoza2019) and for five centers and southern states (Rojas & Jiménez, Reference Rojas and Jiménez2008), both based on self-perception. For Peru, estimates based on the MIQ are available by Monge & Winkerlried (Reference Monge and Winkelried2001) for extremely vulnerable households and Herrera (Reference Herrera2002) for the total population. Colombian subjective poverty is estimated by Pinzón Gutiérrez (Reference Pinzon Gutiérrez2017), Niño-Muñoz (Reference Niño-Muñoz2023), and Tobasura & Casas (Reference Tobasura and Casas2017). The first two studies are based on self-perception and the last one on Minimal Income Question, and only Pinzón Gutiérrez (2006) has national representativity. Estimates are also available for Argentina (Luchetti, Reference Lucchetti2006; based self-perception) and Uruguay (Scalese, Reference Scalese2022; based on the Minimal Income Question).

The studies that compare subjective and objective poverty in the region also find that subjective poverty is significantly higher (Monge & Winkerlried, Reference Monge and Winkelried2001; Luchetti, Reference Lucchetti2006; Rojas & Jiménez, Reference Rojas and Jiménez2008; Tobasura & Casas, Reference Tobasura and Casas2017; Scalese, Reference Scalese2022). Ortiz-Pech et al. (Reference Ortiz-Pech, Alvarez -Marchan and Albornoz-Mendoza2019) find higher subjective poverty in a context where all the households are objectively poor, and Herrera (Reference Herrera2002) finds that in Peru both types of poverty are similar.

As in the international context, the determinants of subjective poverty are studied for some countries in the region. Total household resources (income or expenditure) are identified as a factor reducing subjective poverty (Herrera, Reference Herrera2002; Pinzón Gutierrez, 2006; Rojas and Jiménez, Reference Rojas and Jiménez2008). Other factors positively associated with subjective poverty are undernutrition and violence (Pinzón Gutierrez, 2006). Household size, presence of children, parental education, married couples, and extended households are associated with lower subjective poverty (Herrera, Reference Herrera2002). Rojas & Jiménez (Reference Rojas and Jiménez2008) also find that subjective poverty depends on the expectations regarding income and the comparison with reference groups. In her analysis at the municipal level of Colombia, Niño-Muñoz (Reference Niño-Muñoz2023) centers the attention on the study of the effects of institutions over the perception of poverty. Her results show that having a better rule of law and fiscal performance, reducing political fragmentation to have better governance, guaranteeing property rights, fostering the benefits of metropolitan areas, and improving citizen participation reduce the probability of feeling poor.

Last, two studies analyze the determinants of the discrepancy between subjective and objective poverty in the region. Luchetti (Reference Lucchetti2006) observes that labor flexibility, qualification, and formality increase subjective well-being but not objective one in Argentina. For Uruguay, Scalese (Reference Scalese2022) finds that the probability of discrepancies between absolute and subjective measures is affected by the characteristics of household members (unemployment, informality, education, and immigration), housing and household characteristics, and by the reception of public benefits (food baskets or cash transfers), as well as by the prevailing conditions of the reference group (defined by region of residence and age and education of household head).

5 Data and Methodological Aspects

The tradition of poverty measurement in Latin America is based on the consideration of absolute poverty lines, using the basic needs method. This tradition originated in the pioneering work of ECLAC at the end of the 1970s, which paved the way for the establishment of a common methodology for the region. At present, almost all the countries of the region have government bodies that carry out poverty measurements, using national absolute poverty lines (ECLAC, 2019). At the same time, ECLAC continues to calculate absolute poverty lines for Latin American countries to ensure comparability of poverty results across the region. Through this standardized methodology, based on the cost of basic needs method, ECLAC enables meaningful cross-country comparisons of poverty rates and trends in Latin America.Footnote 10

The World Bank has also tracked global poverty since the early 1990s. Their key goal is to measure poverty consistently across countries, reflecting similar living standards. For Latin American countries, the World Bank threshold corresponds to $3.65 per person per day (PPP) in the cases of Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Paraguay, which are classified as lower-middle-income countries. The corresponding WB threshold is $6.85 per person per day (PPP) in the cases of the upper-middle-income countries of the regions like Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay. The global extreme poverty line of $2.15 per person per day (PPP) applies to all countries, regardless of income level.

In this Element, we report results using national poverty lines to measure objective income poverty, which precludes direct cross-country comparisons. This methodological option is based on the fact that national poverty lines are typically developed with a deep understanding of local economic conditions, cultural norms, and societal expectations. These lines often better represent the social understanding and definition of poverty within each country and are policy relevant, as national governments refer to them to design and implement poverty reduction strategies and social programs. Moreover, these lines generally have greater acceptance and recognition among the country’s inhabitants. However, to ensure the robustness of our findings, we also conduct parallel analyses using the ECLAC and World Bank poverty lines, recognizing its value as a standardized measure for cross-country comparisons.

This study is based on surveys that include questions regarding subjective poverty. In the cases of Brazil (2017–2018), Colombia (2016–2017), El Salvador (2005–2006), Paraguay (2011–2012), and Uruguay (2016–2017), expenditure and income surveys are used. For Ecuador (2013–2014) we use the life conditions survey, and for Peru (2018) we use the National Household Survey. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the surveys mentioned here.

Table 1 Characteristics of surveys

| Country | Survey | Year | Coverage | # households |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Household Budget Survey | 2017−2018 | National | 65,800 |

| Colombia | National Household Budget Survey | 2016−2017 | National | 86,222 |

| Ecuador | Life Conditions Survey | 2013−2014 | National | 28,970 |

| El Salvador | National Survey of Household Income and Expenditure | 2005−2006 | National | 4,381 |

| Paraguay | Survey of Income and Expenses and Living Conditions | 2011−2012 | National | 5,288 |

| Peru | National Household Survey | 2018 | National | 33,900 |

| Uruguay | National Survey of Household Income and Expenditure | 2016−2017 | National | 6,880 |

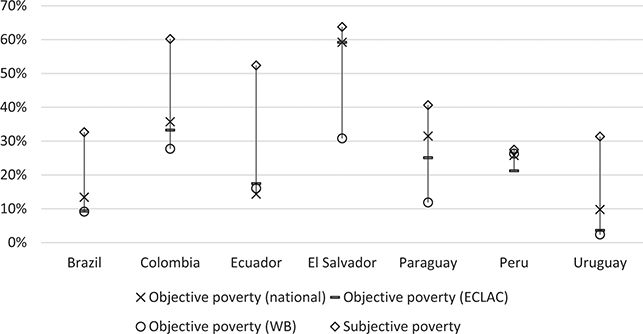

Although all the countries in our analysis are classified as middle income, significant differences emerge in their social contexts, reflecting the diverse socioeconomic landscapes within this broad category. Table A.1 summarizes various social and labor market indicators for the seven countries, revealing a consistent grouping pattern that underscores the heterogeneity of middle-income nations. At one end of the spectrum, El Salvador stands out as the most disadvantaged country in our analysis, with the highest poverty rates (exceeding 50 percent), lowest female labor participation (43 percent), and lowest Human Development Index (0.64). These figures paint a stark picture of the challenges faced by El Salvador in terms of economic development, gender equality, and overall quality of life for its citizens. The high poverty rate, in particular, suggests deep-rooted structural issues. In contrast, Uruguay emerges as the most advantaged country across almost all indicators, boasting a poverty rate of 4 percent, female labor participation of 58 percent, and a Human Development Index of 0.81. Peru follows closely, with a poverty rate of 17 percent, female participation of 64 percent, and a Human Development Index of 0.77, indicating substantial progress in social development and gender equality in the labor market. The remaining countries occupy an intermediate position, characterized by poverty rates ranging from 21 percent to 31 percent, female labor participation between 54 percent and 59 percent, and Human Development Index scores between 0.71 and 0.76. This middle group demonstrates the complexity of development trajectories as these nations have made significant strides in some areas while still facing considerable challenges in others. Notably, these countries also exhibit the highest inequality within our sample, as measured by the Gini coefficient. This suggests that while these nations have achieved a certain level of overall development, the benefits of this progress may not be evenly distributed among their populations.

The absolute poverty lines we are considering are constructed by the National Statistical Offices in each country, following the cost of basic needs method, except for Brazil. As Brazil does not have an official poverty line, we follow the usual practice in the literature and consider half minimum wage as the poverty line. Details about the absolute poverty thresholds and their calculation in each country are presented in Table 2. As explained, our choice of the national poverty lines as the basis of our analysis is derived from the consideration that these lines express more accurately the social sense of poverty than other poverty thresholds. Despite this, and as a robustness check for our results, we also perform the calculations using ECLAC’s poverty lines, and report the main results in the Appendix.

Table 2 Objective absolute poverty lines for selected Latin American countries

| Country | Poverty line construction |

|---|---|

| Brazil | Brazil does not have an official poverty methodology. To construct a per capita poverty line, half the value of the minimum wage is usually taken as a reference. |

| Colombia | The poverty line is the minimum per capita cost of a basic basket of goods (food and nonfood) in each geographic area, based on the 2016−2017 National Household Budget Survey. |

| Ecuador | The fifth round of the Quality-of-Life Survey (ECV) conducted in 2006 was used to draw both the official extreme poverty line, which reflects a minimum threshold of 2,144 Kcal per person per day, and the official moderate poverty line, which uses an Engel coefficient of 56 percent. The poverty lines are updated across time using the total CPI. |

| El Salvador | The country uses the Cost of Basic Needs method for the poverty estimates, providing two estimates: (i) extreme poverty (the cost of a basic consumption basket that would allow household members to consume a minimal amount of calories) and (ii) moderate poverty (the cost of an extended consumption basket, equal to twice the value of the basic consumption basket). The official line used by El Salvador was constructed in 1982 and was based on food spending patterns from the 1976 Family Budget Survey. |

| Paraguay | The extreme poverty line corresponds to the monetary value of the basic food basket, which reflects minimums thresholds of 2117 and 2291 Kcal for urban and rural regions. The value of the total poverty line is equal to the value of the extreme poverty line multiplied by the Engel coefficient, which is 38 percent for urban regions and 48.8 percent for rural areas. The structure of the basic food basket and the basic consumption basket was updated following the 2011−2012 Income and Expenditure and Living Conditions Survey. |

| Peru | Peru uses monetary poverty lines to measure extreme and total poverty with per capita consumption as the welfare measure. The total poverty line represents the minimum cost of acquiring a basket of goods and services necessary to achieve adequate living conditions, and this basket varies by geographic region as well as by rural and urban areas. It was constructed based on the 2010 National Household Expenditure Survey. |

| Uruguay | The poverty line corresponds to the updated monetary value of the basic food and nonfood baskets considering economies of scale for the nonfood expenditures introduced by geographical area. The poverty line is constructed based on Household Consumption and Income Survey of 2005−2006. |

To elaborate the SPL, we follow the method discussed in Section 2. In our case, the control variables considered for the estimation include household income, number of members of the household, age of the head of household and its square, binary variables identifying female household head, non-white household head and urban households, marital status of household head, household type, and years of education of the household head (see Table A.2).

Once we classify households in terms of objective and subjective poverty, we evaluate the correlation and overlapping of both measures. With this objective, we calculate the Cramer V correlation between both types of measure and redundancy coefficients, following Santos & Villatoro (Reference Santos and Villatoro2018).

Given two poverty measures,

![]() and

and

![]() , the Cramer´s V coefficient is calculated as

, the Cramer´s V coefficient is calculated as

(5)

(5)

where

![]() is the proportion of people nonpoor in both

is the proportion of people nonpoor in both

![]() and

and

![]() ,

,

![]() is the proportion of people poor in both

is the proportion of people poor in both

![]() and

and

![]() ,

,

![]() is the proportion of people poor in

is the proportion of people poor in

![]() but not in

but not in

![]() , and

, and

![]() is the proportion of people poor in

is the proportion of people poor in

![]() but not in

but not in

![]() .

.

![]() and

and

![]() are the proportions of people poor in

are the proportions of people poor in

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively, whereas

, respectively, whereas

![]() and

and

![]() are the proportions of people nonpoor in

are the proportions of people nonpoor in

![]() and j, respectively. In other words, the Cramer’s V is defined as the product of matches minus product of mismatches adjusting for the marginal distribution of the variables.

and j, respectively. In other words, the Cramer’s V is defined as the product of matches minus product of mismatches adjusting for the marginal distribution of the variables.

The redundancy measure

![]() is a more precise indicator showing the matches between deprivations in both measures as a proportion of the minimum of the two poverty measures.

is a more precise indicator showing the matches between deprivations in both measures as a proportion of the minimum of the two poverty measures.

(6)

(6)

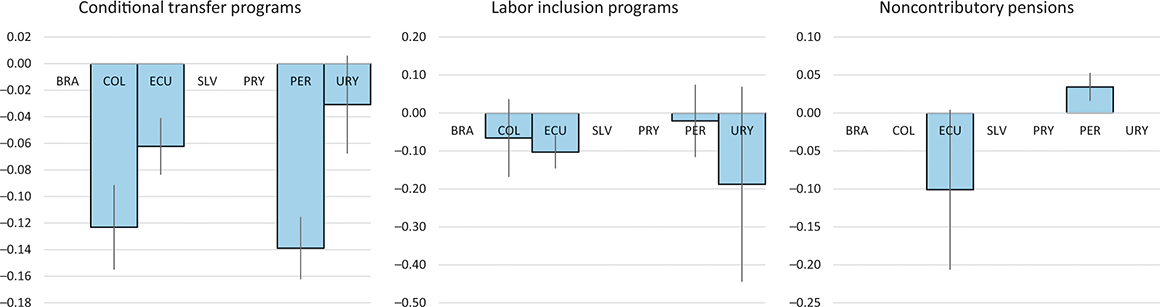

Finally, to analyze the concordance between households classified as poor under the subjective and objective approaches, we use a probit model. This allows us to identify the factors associated with the lack of agreement between these measures. As discussed in Section 6.3, our results indicate that the largest discrepancies occur among households that are not poor in objective terms but consider themselves as poor, that is, they are subjectively poor. For this reason, our probit model takes the set of households that are not poor in absolute terms and investigates the factors associated with their perception of themselves as poor.

6 Subjective and Objective Poverty

We present our main results in three subsections: first the estimations of the SPL and the comparison with the objective poverty lines in Latin America, second the comparison of poverty prevalence, last the results for the subjective poverty and the superposition with national poverty lines.

6.1 Subjective and Objective Poverty Thresholds in Latin America

Our SPLs are estimated based on models with control variables, presented in Table A.2. The results of the models are as expected in the seven countries; the minimum household income is positively related to the perceived household income and with the number of household members. The other control variables also show the expected behavior. In general terms, the minimum income is positively related with the age of the household head (in decreasing terms) and with their education, and negatively related to female and non-white household heads. The result that households with reference persons with less education report needing less than those with higher education has been interpreted as a reference group effects (Garner & Short, Reference Garner and Short2003). Also, households with a married or cohabiting head are associated with higher minimum income answers than singles, while the evidence for separated, divorced, and widows or widowers is not conclusive across countries. All the household types are associated with higher minimum income than unipersonal households, especially couples with children and extended households (with relatives). These results go in the same line as De Vos & Garner (Reference De Vos and Garner1991) (age), Garner & de Vos (Reference Garner and de Vos1995) and Garner & Short (Reference Garner and Short2003) (education), and Danzinger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984) (female household head).

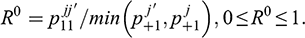

Using the coefficients derived from the previous estimation, the SPL is constructed by substituting them in equation (4). Thus, we obtain a different value of the line for each household depending on its characteristics. In Figure 1, we compare the SPL by veintiles of per capita income of the country with the minimum income (MIQ) declared by the households. Both variables are expressed in PPP dollars of 2015.

Figure 1 Minimum income question (MIQ) and subjective poverty line (SPL) by per capita household income.

Notes: Minimum income question and SPL expressed in 2015 PPP dollars. Per capita household income in ventiles.

The minimum income increases with household per capita income in all the considered countries, which is consistent with Goedhart et al. (Reference Goedhart, Halberstadt, Kapteyn and Van Praag1977) and Danziger et al. (Reference Danziger, Van der Gaag, Taussig and Smolensky1984). In all the countries, households with income over the median (ventile 10 and over) tend to overestimate the minimum necessary income as it is higher than the SPL, even after adjusting for all the included controls. Overestimation increases with income and is particularly high for households of the higher deciles. The behavior in the lower half of the distribution is not consistent across countries. In general terms, poorer households declare a minimum income that is close to or slightly under the SPL.

The comparison between the objective and SPLs reveals systematic differences. As shown in Table 3, the average SPL is almost always higher than the objective poverty line, as reported in almost all the previous research. The difference is higher when ECLAC or World Bank thresholds are considered, given that those poverty lines are lower than national poverty lines, except for Ecuador. The range of variation of the absolute poverty lines between countries is much smaller than that of SPLs. The average SPL is between 8 percent and 167 percent higher than the national objective poverty line, depending on the country, with these extremes corresponding to Paraguay and Ecuador. Only in Peru both thresholds are virtually equal, consistent with previous results for the country (Herrera, Reference Herrera2002).

Table 3 Subjective and objective absolute poverty lines. Average values (2015 PPP dollars)

| Objective – Absolute | Subjective | Percent difference (Sub.-Obj.) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | ECLAC | WB | National | ECLAC | WB | ||

| Brazil | 624 | 517 | 496 | 1211 | 94% | 134% | 144% |

| Colombia | 726 | 654 | 553 | 1157 | 59% | 77% | 109% |

| Ecuador | 565 | 657 | 606 | 1510 | 167% | 130% | 149% |

| El Salvador | 858 | 859 | 400 | 926 | 8% | 8% | 131% |

| Paraguay | 843 | 690 | 374 | 1056 | 25% | 53% | 182% |

| Peru | 661 | 585 | 621 | 660 | 0% | 13% | 6% |

| Uruguay | 918 | 582 | 465 | 1539 | 68% | 165% | 231% |